In 2013, “Washoku” (Japanese cuisine) was inscribed on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage for its culinary heritage rooted in respect for nature and the seasons as well as for the sustainable use of resources. Japanese cuisine has attracted the attention of chefs around the world for its simple yet elegant and balanced dishes, prepared from a wide range of local seasonal ingredients. The Japanese government has even designated November 24 as “Washoku Day” to ensure that these skills and knowledge are passed on to future generations.

In addition to its reputation for refined cuisine, Japan is also known for being one of the longest-living countries in the world, thanks in part to a healthy plant-based diet. You may have heard of Japanese seaweed such as nori (a dried edible seaweed made from a species of red algae, often used to wrap sushi rolls or onigiri), wakame (native to the cold temperate coasts of the northwestern Pacific Ocean, this seaweed has a subtly sweet but distinctive and strong flavor, and is most often served in soups and salads), hijiki (a brown sea vegetable growing wild on the rocky coasts of East Asia, rich in dietary fiber and essential minerals such as calcium, iron and magnesium), or the famous agar (a gelatinous substance composed of polysaccharides obtained from the cell walls of certain species of red seaweed, commonly used as a dessert ingredient throughout Asia).

This article will focus on the equally popular kombu, a variety of edible kelp, which will have no secrets by the end of your reading. Being surrounded by the ocean, Japan has developed its food culture based on kombu since ancient times. Called the “king of seaweed”, kombu is an essential ingredient in Japanese cuisine, giving it that authentic Japanese taste. Very nutritious, it is the most important ingredient used to prepare the Japanese soup broth “dashi”. After introducing kombu in all its aspects, we will travel to Shikabe, a small port town that has developed local tourism based on the production of this algae. If, like me before writing this article, you have little knowledge of kombu, don’t worry! What is kombu? Why has this seaweed become the mainstay of Japanese cuisine? I will tell you all about this superstar of Japanese cuisine in the next few paragraphs.

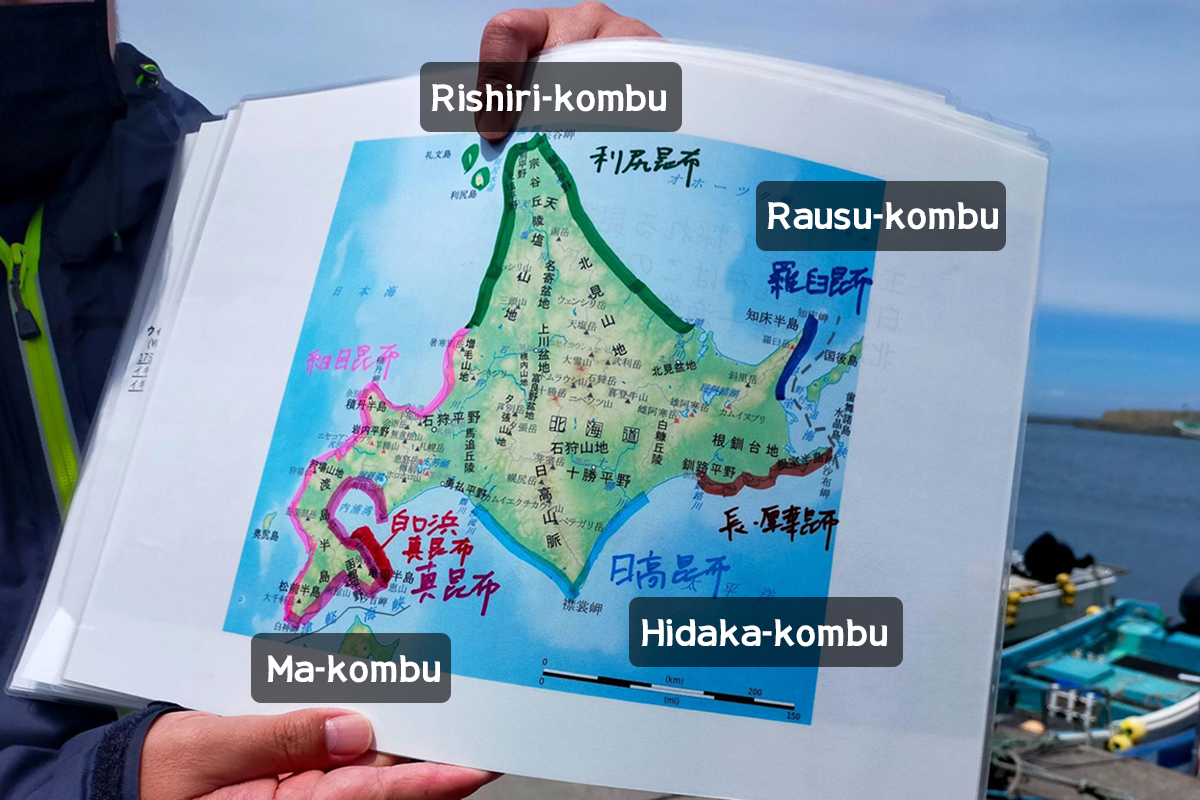

The study of the remains of Ofune, in Minamikayabe (situated 14km from Shikabe town) of a settlement dating back to the Jomon period (about 14,000 to 400 BC), revealed that the Japanese were already consuming kombu in the Jomon period. The word kombu is probably derived from kompu, an Ainu word referring to things that grow on underwater rocks. The term appears in Chinese documents as early as the third century and may have been introduced into the Chinese language through trade with Ainu inhabited areas. Kombu refers to a large variety of edible kelp or seaweed, most of which belong to the Laminariaceae family, and has been a source of food in Japan for over 1,000 years. In early times, konbu was consumed as a source of salt by simmering it until it lost its shape. The custom of making broth with kombu is thought to have originated around the tenth century. Kombu is found not only in Japan, but also in Russia, China, Tasmania, Australia, South Africa, the Scandinavian Peninsula and Canada. However, the Japanese are the largest consumers of kombu in the world and of the 22 varieties of this type of algae, 12 are found in Japan. Hokkaido, which is the main fishing area for all these varieties with about 90% of the total production, is generally considered the kombu garden of the world. The sea ice that drifts from Siberia to Hokkaido, rich in minerals, provides a suitable environment for the production of delicious kombu (for more information on the phenomenon of drift ice, you can read the very interesting article: Shiretoko: The Peninsula at the End of the World https://hokkaido-treasure.com/column/012/ ). The precursor of Hokkaido kombu came from the far east of Russia. Since then, kombu has spread to the coastal areas of Hokkaido and many places produce kombu, such as the islands of Rishiri and Rebun in northern Hokkaido or Rausu in eastern Hokkaido. It has also diversified into several varieties and each type of kombu has slightly different flavors and textures. These different kombu are used differently in Japanese cuisine depending on their specific characteristics.

There are 4 major varieties of kumbu :

Ma-kombu, harvested around Hakodate and northern Tohoku (Shimokita Peninsula in Aomori Prefecture) is a thick dried seaweed, much longer and wider than other types of kombu, with a characteristic mellow taste. The broth made from this seaweed is clear, delicate and aromatic. It is the highest rated and most popular type of kombu, frequently used by Kaiseki chefs in Japan to make a remarkably tasty dashi broth for soups, noodle dishes and stews. The local Matsumae clan used to offer this variety of kombu to the imperial court and the Edo shogunate. Rishiri-kombu, harvested on the islands of Rishiri and Rebun, is thinner than ma-kombu and is finely wedge-shaped near the stem. The leaves are dark brown and hard, with a sweet and salty taste that makes the dashi rich, tasty and clear. It is particularly popular in tea ceremony dishes in Kyoto. Rausu-kombu, harvested in the Rausu region of the southern Shiretoko Peninsula, has a fragrant and mild taste. Mainly used to make broth, it is also made into kombucha tea. Hidaka kombu, from the Hidaka area in southern Hokkaido, is popular with many people because of its reasonable price and reliable quality. It is also used as an ingredient in commercially available rice balls.

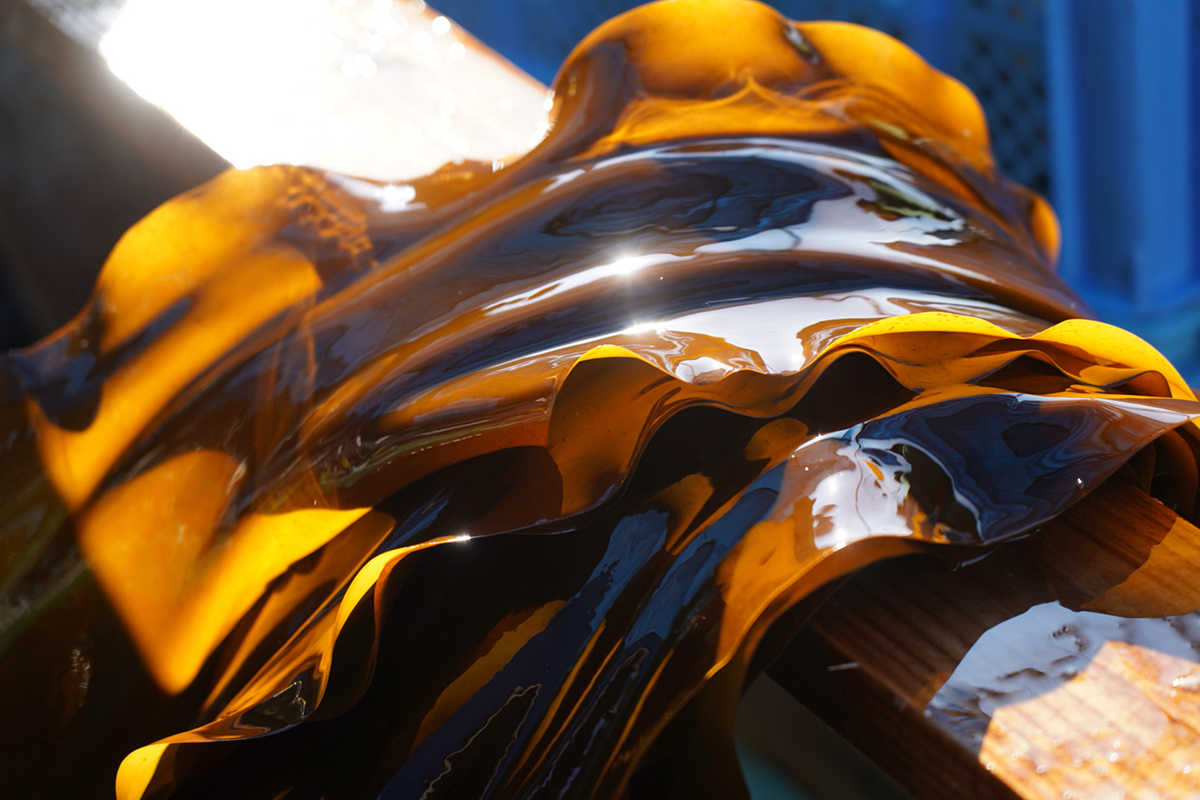

Kombu grows in the cold ocean waters off Hokkaido at depths of 5~7 meters through photosynthesis. It usually takes about two years to reach the maturity level required for harvesting. It is quite a long period and years of high and low production make the kombu business unstable. In addition, its beds are slowly being depleted. So in addition to the natural production of kombu, it is produced artificially to meet the needs. The first step in kombu cultivation is the germination of spores, which are sown in ropes that are then attached to a frame. The cultivation of kombu does not actually involve any feeding or fertilization as it simply grows on its own, incarnating the wonderful power of the ocean and the sun to nurture life. It can grow 10 centimeters in a single day !

Harvesting usually takes place over a short period of 2 to 3 months, during the months of July to September, and is traditionally carried out by kombu fishermen in boats. Wild kombu is subject to severe harvesting restrictions to avoid overexploitation. Restrictions differ from region to region, and in some regions fishermen can only harvest kombu on average 4-5 days per week, up to a maximum of 25 days, between late July and September. Harvesting is interrupted on stormy days, resulting in a red flag being raised on the beach early in the morning. This is called “okiage”, which can last for days in some years. So when they get the go-ahead, the fishermen harvest kombu in a wild frenzy for the half day they have.

In general, fishermen catch kelp using a hoko, a long pole that is several meters in length and equipped with a hook at the end to detach the kombu from the seabed above the root level. The boats return to shore loaded to the brim, and the women spread the konbu on the beach to dry in the sun. On a hot summer day, this process can be completed in four to five hours. Once dry, the kombu is brought inside, each leaf is cut and its shape adjusted, and then it is shipped mainly to the Osaka area. The kombu seaweed harvested in Hokkaido was once transported by boat along the kombu route (moving westward along the coast of the Sea of Japan) to Osaka, which has been a kombu trading center since that time. Therefore, kombu seaweed wholesalers and processors are mainly located in or near Osaka. Some kombu also undergoes an additional maturation process called kuragakoi (cellar storage). This process improves the flavor of kombu and removes its characteristic seaweed smell.

When harvesting kombu, the root of the kombu is not touched, but only the upper part of the “leaf”, so that the base of the kombu can grow back. It is a renewable food resource par excellence and not only that! Since kombu is a large algae, it is efficient at photosynthesis and absorbs about five times more carbon dioxide than Japanese cedar. Marine afforestation helps to reduce global warming in the same way as tree planting. They can also play a role in ocean purification, cleaning up oil-contaminated waters in about seven years. Kombu beds are true “marine forests”. They support the life of marine organisms, for example by providing a habitat for small fish and serving as a spawning and feeding ground.

Kombu is processed and used in different ways:

Tsukudani-kombu (cut into thin strips or squares, boiled in soy sauce and sugar, eaten with rice or wrapped in onigiri), Shio-kombu (cut into squares or thin strips lengthwise, boiled in water, soy sauce, mirin and sugar, and sprinkled with seasonings such as salt, eaten with rice or used in ochazuke, a simple Japanese dish prepared by pouring green tea, dashi or hot water over cooked rice), Tororo-kombu (pickled kombu, softened, layered, pressed and finely grated. It is used in soups such as miso soup, udon and soba, or eaten over rice or wrapped in onigiri). Below you can see the Rishiri ramen with tororo-kombu. It was so yummy, yummy !, Oshaburi-kombu (cut into small pieces for a crunchy snack, rich in Umami flavor that can be eaten with the fingers), etc.

But its most common use is Dashi-kombu (sun-dried and cut into pieces suitable for making broths).

As I mentioned earlier in this article, the Japanese were already consuming kombu in the Jomon period. About 16,500 years ago, the Jomon hunter-gatherers of northern Japan invented pottery, a technology that revolutionized cooking. And even today, fish and vegetable stews are typical of Japanese cuisine, whether it is home-style or gourmet. There are many varieties of dashi, which vary from region to region. The most common are kombu (the star of our article – I’ll come back to it later), shiitake (edible mushroom), katsuobushi (skipjack tuna or bonito flakes), niboshi (small sardine), yakiago (flying fish) and shrimp. These ingredients are usually dried, but depending on the fish, the process may first involve boiling, grilling or smoking. Then the preserved ingredients are soaked in cold or hot water for varying lengths of time to extract the broth, which is added to soups, stews, sauces, as well as dishes such as okonomiyaki (a type of pancake containing meat or fish and vegetables) and chawanmushi (a tasty egg cream).

Shojin ryori is a type of vegetarian cuisine introduced with Buddhism during the Heian period (794-1185). The ingredients used in shojin ryori consist entirely of vegetables and soy products, and kombu dashi is essential to enhance the taste. A dashi made from kombu and katsuobushi was developed around the 7th century. Perfected over the years, it has become Japan’s most indispensable cooking stock. Without exaggeration, it can be said that dashi is the heart of Japanese cuisine, as it enhances and harmonizes the flavors of other ingredients.

The dashi used in Japanese cooking is very easy to make. I invite you to watch this video and why not try it at home!

You can’t talk about dashi without talking about umami. If you try kombu dashi in its purest form, a light and subtle taste will fill your mouth. What makes dashi so indescribably delicious is the umami! The term umami was coined by Kikunae Ikeda.

In 1907, while tasting a bowl of tofu boiled in kombu dashi, the Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda (1864-1936) became aware that there was another fundamental taste that was totally different from the four existing tastes of sweet, salty, sour and bitter. Intrigued, he named this taste umami, which means “essence of pleasure” in Japanese, and began to analyze the composition of kombu dashi. In 1908, he isolated crystals that conveyed the taste he had detected, composed of glutamate, an amino acid that is one of the building blocks of proteins. Glutamate is naturally present in the human body and in many delicious foods we eat every day, including aged cheeses, cured meats, tomatoes, mushrooms, salmon, steak, anchovies, green tea, etc. We all have umami enhancers in our pantry: ketchup, truffle oil, ranch dressing, miso and soy sauce, etc. Kombu contains a higher percentage of glutamic acid than any other food in the world. Washoku (Japanese cuisine) has a tradition of cherishing each season. By using umami, chefs bring out the flavors of these seasonal ingredients. While respecting tradition, they are dedicated to innovation.

At the same time, but on the other side of the world, Julius Maggi, a Swiss entrepreneur and food industry pioneer, was developing fast-cooking dehydrated soups. Maggi’s work eventually led to the creation of bouillon cubes made from hydrolysed plant proteins – it is the hydrolysates that give the bouillon its meaty taste. Both Professor Ikeda and Maggi worked with soup stock to determine its components. But although both men have developed soup broth products, the amino acids in their soups are different.

Let’s travel to Shikabe, located in Oshima Prefecture, only 62 kilometers north of Hakodate City, facing Uchiura Bay and next to the beautiful nature of Onuma Quasi-National Park (To get a better idea of the charms of Onuma, I invite you to take a look at this article: Onuma Quasi-National Park: Enjoying the Autumn Leaves in Hokkaido https://hokkaido-treasure.com/column/031/). Its location makes it an ideal destination for a day trip from Hakodate. Let’s explore the kombu tourism of this small fishing town of about 3,000 people called Shikabe.

Shikabe is derived from the Ainu word “sikerpe”, which means “place where the cork of the Amur is found”. The Shikabe flag consists of four カ (-shi means 4 in Japanese and カ is for the -ka of Shikabe) surrounding the red onsen symbol inside two kombu algae.

The town of Shikabe is a non-agricultural land and most of the inhabitants live from fishing. This small fishing town has no less than 300 fishing groups. In addition to kombu production, octopus, sea urchins with an intense jewel color, sweet aroma and unrivaled creaminess, called Ezo-bafun uni (Ezo is the traditional Japanese name for Hokkaido, which was called Ezo until June 1869), and tarako (roe of Alaskan hake, a kind of cod. The town even holds a festival called Cod Lips in honor of their delicious tarako. See a picture of me with the tarako mascot ! ) are caught here.

About 25 km from Shikabe town stands the majestic Mount Komagatake, a 1,131-meter-high active volcano and the symbol of Oshima Prefecture. The mountain had a conical shape like Mount Fuji until the top collapsed in the great eruption of 1640. Volcanic eruptions are a blessing for the marine environment, as the lava and volcanic rocks are rich in iron, as well as magnesium and silicates, which provide nutrients that contribute to a rich marine environment. Thanks to the Komagatake volcano, the town is not only popular for its seafood and kombu, but also for its 30 hot springs (onsen) and the town is home to many Japanese inns with their own private onsen water.

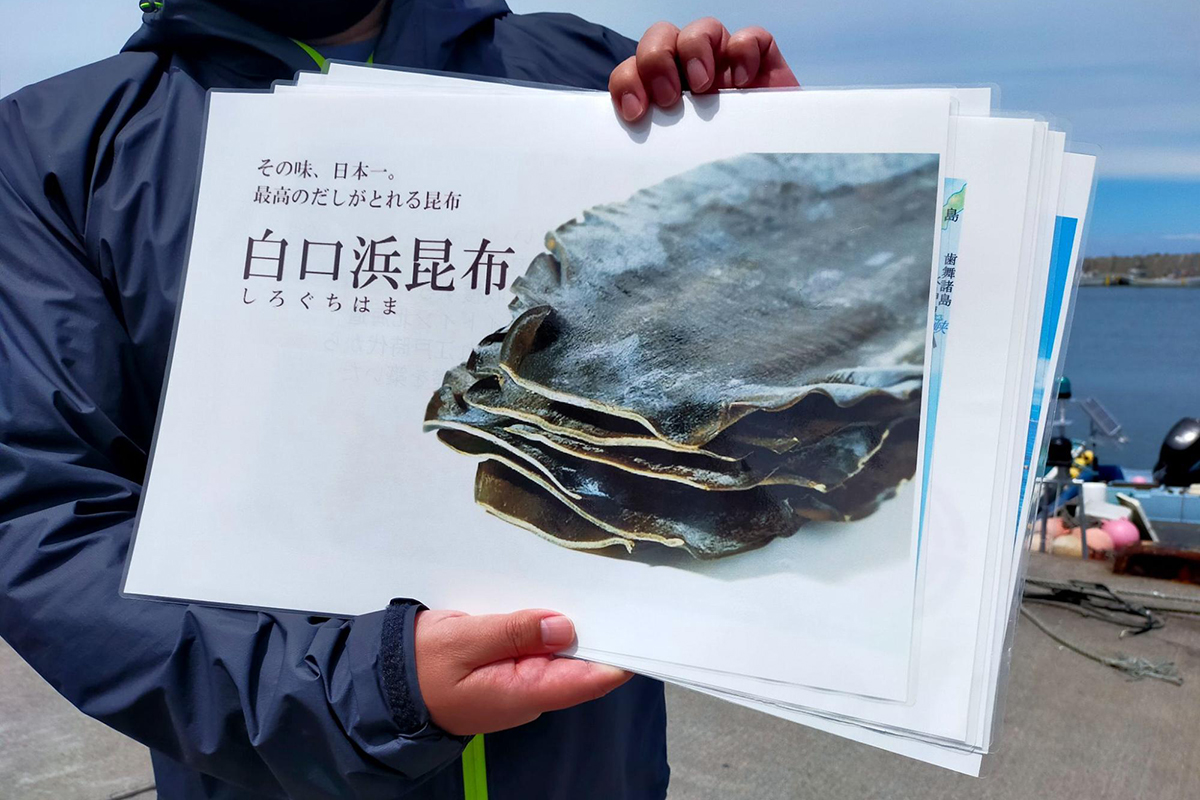

In this small off-the-beaten-path port town, you can participate in a unique cultural experience. If you visit Shikabe during the kombu harvesting period from July to September, you can learn from a local guide about the life of local fishermen and the behind-the-scenes of local kombu production. Shikabe kombu has been called “Shiraguchihama kelp” since the Kitamaebune era (To know more about it, you can refer to this article History of Hokkaido: Kitamaebune cargo vessels in Matsumae and Esashi : https://hokkaido-treasure.com/column/024/ ) because it is thick and the cut end looks white. The city is the main kombu producing region in Japan, accounting for 15% of the national kombu production. Like kombu from other regions of Hokkaido, most of Shikabe’s kombu is shipped to the Kansai and Hokuriku regions (the northwestern part of Honshu), where there are many processing manufacturers, as it is suitable for processing in abundance into high quality salted kombu as well as refined and clear kombu.

Shikabe kombu is also known as “gift kombu” because the Matsumae estate used to give it to the imperial court and the shogun’s family. This kombu, which is sweet even when eaten as is, was prized as a confectionery at the court and by the generals. Before boarding a fishing boat (the tour may be canceled due to weather conditions, as on the day of our visit due to strong winds) to observe the kombu growing in the sea and to meet the fishermen, the guide will show you the harbor and give you some explanations about the city itself and its kombu.

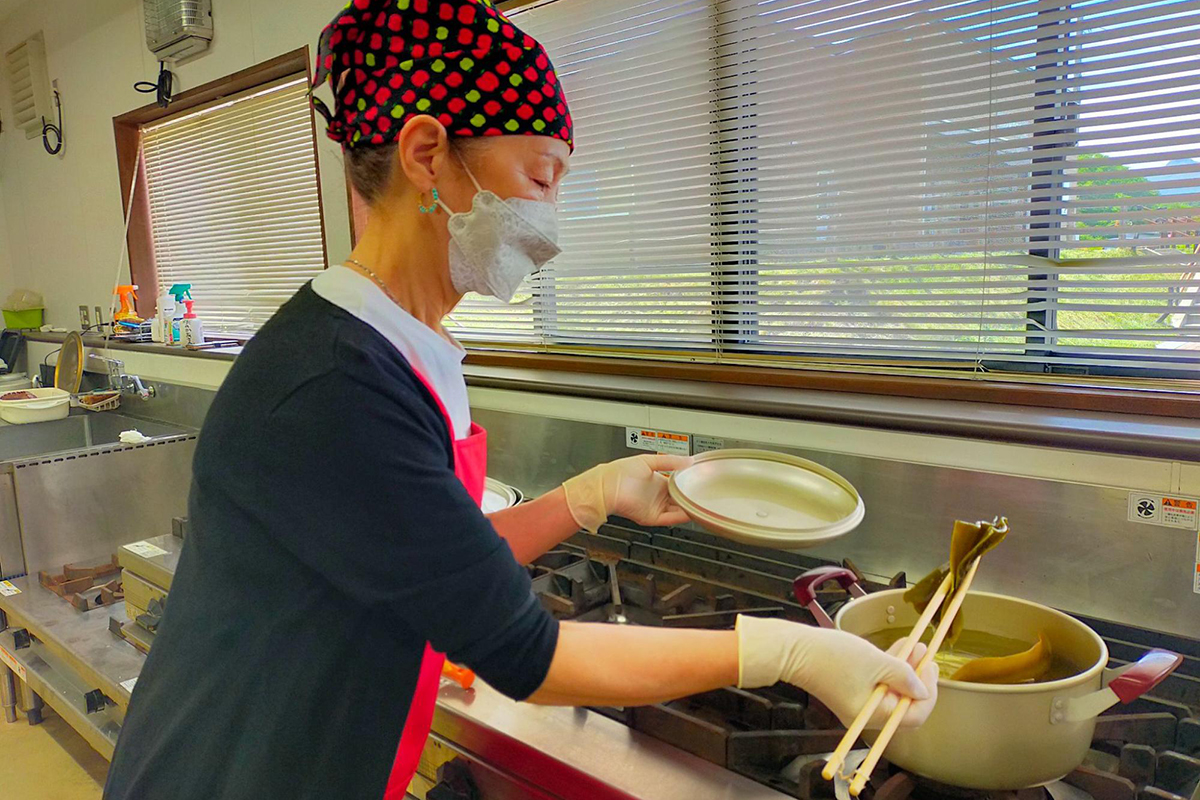

Then, after learning about all aspects of kombu, from its original seaweed-based version to its dried version, in the company of the local guide and fishermen, it’s time to meet the women of Shikabe for another cultural adventure you can enjoy all year round: a private cooking class with these lovely fishermen women. You will learn how to cook fresh seafood (including kombu, of course!) caught by local fishermen. While cooking typical Japanese dishes, you will interact with these women who will share with you their daily life and their cooking recipes. More than just a culinary experience, this is an authentic way to learn about the traditional way of life of Japanese fishermen.

During our visit with my new colleague Jordan (If you are curious to know more about her, please visit her profile: https://hokkaido-treasure.com/aboutus/jordan/ ), we were greeted by two lovely fishermen’s wives.

After putting on an apron, we cooked fresh octopus, caught that morning by the husband of one of the women. The two women prepared the octopus while it was still alive by killing it, dismembering it, cleaning it and removing the inedible parts. After dismemberment, the tentacles were still moving, which was pretty impressive! After preparing the octopus, we cooked it in two dishes: octopus in sashimi (raw fish) and octopus prepared in a sauce made of lots of mayonnaise and hake roe. Yummy…yummy !

Then, we cooked different processed kombu in 2 dishes. With a very young and soft dried kombu (the green kombu in the basket in the picture below, which was soaked in water beforehand), we prepared a Japanese one-pot dishes with boiled daikon (Japanese radish), carrots and pork. We tied the kombu so that it would not get damaged during the simmering process, so that it would be easier to handle with chopsticks during the meal and also so that the plate would be nicely presented. With a harder kombu (in the right basket on the picture below) we prepared the traditional miso soup. The kombu was soaked in water for about an hour, then we heated it up and just before the broth boiled, we removed the kombu and added the miso paste and the different ingredients to complete the soup like wakame and leek.

We then enjoyed the taste of our own cooking around a lively table. I must say it was good and I might consider becoming a cook!

And what better way to end lunch than with a cup of coffee and a view of the blue sea!

I am sharing some links for you to try to cook some kombu recipes at home. Please share on our facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/hokkaidotreasure ) your comments about it !

If you would like to visit the Hakodate area, including Shikabe, to fully immerse yourself in the Japanese kombu culture, please contact us. We will be happy to help you create a unique vacation full of original activities and personalize your visit by adding a meal at an extraordinary sushi restaurant or a canoe ride on the waters of Lake Konuma with the silhouette of Mount Komagatake in the background.