Spring has definitely won over winter in Sapporo, but we are in that in-between period waiting for the greenery to appear. This transitional period, which can be associated with the typical Japanese tradition of koromogae (衣替え, seasonal change of clothes), is perhaps not the best time to enjoy Hokkaido’s nature. The landscape has lost its beautiful white coat, giving way to a lifeless landscape with bare trees while nature is quietly and discreetly preparing to come back to life. It is no longer winter, but the spring atmosphere is not fully there yet. Fortunately, there is much more to enjoy in Hokkaido than its incredible nature and outdoor activities! Now that you know me a little better (If it is not the case, you can quickly check my profile: https://hokkaido-treasure.com/aboutus/aurore/) and my sweet tooth is no longer a secret, you may not be surprised that I’m taking you on a gourmet journey to Otaru, Sapporo’s neighboring city. You may think you know everything about this charming port city, but how about accompanying me on a time travel by visiting the old traditional shops of mochi, those delicious Japanese rice cakes!

For this little gourmet gateway to Otaru, I was accompanied by my colleague Eriko Kakudate (https://hokkaido-treasure.com/aboutus/kakudate/), who specializes in gourmet tours. Otaru is well known as a gourmet city, especially for its seafood, but as Eriko loves retro cafes and is familiar with traditional Japanese tea and sweets, she was eager to share some of the Otaru’s best mochi stores only known by locals, with us! Let’s discover a new facet of the port city of Otaru by immersing ourselves in its history related to one of the most famous Japanese sweets, the mochi. The city has long-established mochi stores with a history of more than 100 years. Get ready, this article is all about gourmet sweets and will make your mouth water…

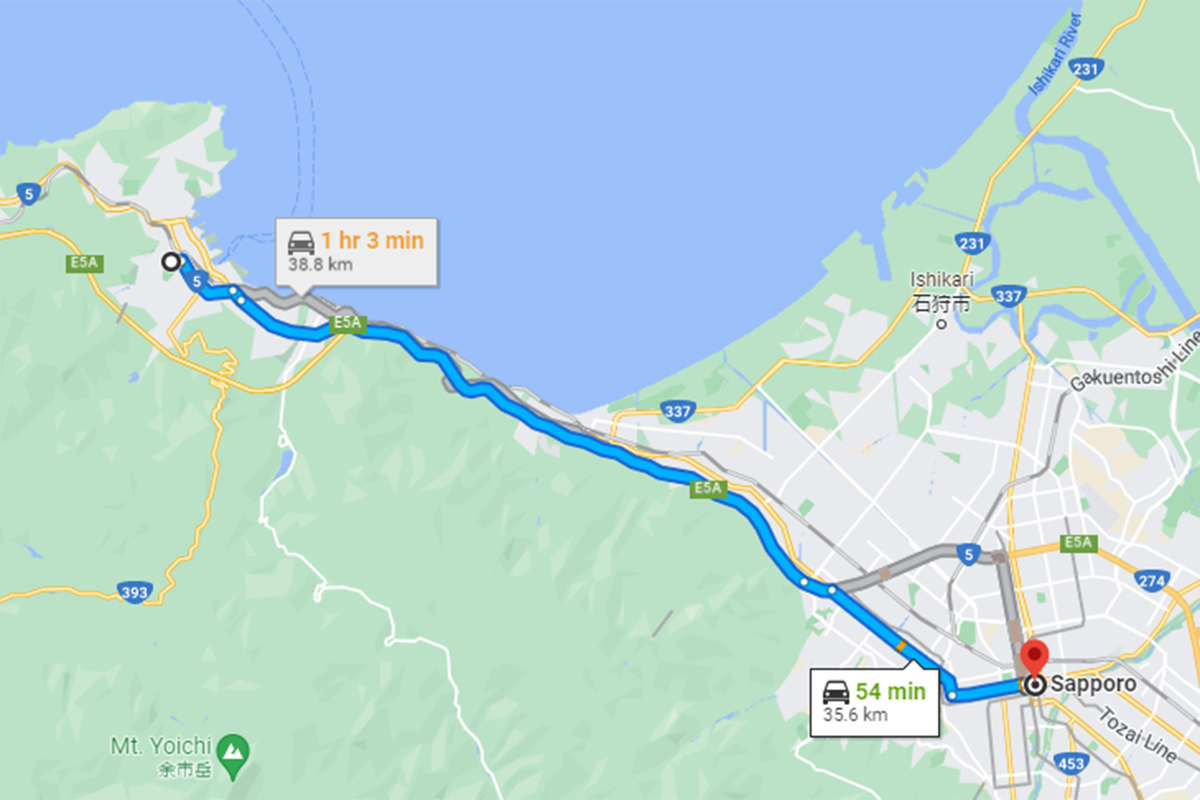

Otaru is a port city located about 40 kilometers northwest of Sapporo. It is a very popular destination for Sapporo residents as well as for foreign visitors. Traveling by train or car from Sapporo is particularly pleasant as this town is situated on the coast of the Sea of Japan and we can enjoy beautiful blue sea scenery. The city offers an interesting contrast between the sea and the mountain landscape. One part of the city is very steep and this part of the city on the mountain slopes is called Saka-no-machi, or “Hill town”. I really enjoy a visit to Otaru because it always feels like a vacation!

Before starting our gourmet walk and tasting mochi, mochi… and more mochi at six different local stores, let me briefly introduce you to the historical background of Otaru city, which is related to the rice cake culture. Why are there so many rice cake stores in Otaru, which had more than 100 in its golden age? And why did these Japanese rice cakes become particularly popular in Otaru, especially at a time when Hokkaido was not yet arable land and rice could not be harvested there?

Otaru, like most of the rest of Hokkaido, was inhabited by the Ainu, the indigenous people of Hokkaido. The name Otaru comes from the Ainu language Ota ol Nai, which means “a river on a sandy beach”. Japanese from the main island of Japan, called Wajin, began migrating to Hokkaido in the 18th century and as they conquered and dominated the territory, Ainu culture disappeared from Otaru, except for many place names derived from the Ainu language and some archaeological remains. With the arrival of the migrants, merchant ships called kitamae-bune developed, supplying the migrants with basic necessities, but also carrying goods for the Ainu who traded with the Wajin of the main island. The ships left from Osaka, sailing from port to port in the Seto Inland Sea to Hokkaido and the journey took between 50 and 60 days. As these trading ships generated huge profits, they made only one voyage per year, which started in spring as the sailing ships depended on the wind.

In 1865, Otaru was a fishing village of just over 1,000 inhabitants, whose economy was based on herring fishing. The herring era ended in the 1950s. Until then, this activity brought considerable wealth to the economy of Otaru. It should be noted that 90% of the herring catch was not used as food but as fertilizer, produced by pressing the boiled herring.

In 1869, when the Hokkaidō Development Commission was established in Sapporo, Otaru became the most important port for the development of Hokkaido. The city then flourished as the financial and commercial center and trading port of Hokkaido. From this period onwards, kitamae-bune owners began to store their goods, Hokkaido-made products and daily supplies from the main island, in warehouses. Built of stone and with a wooden frame, these warehouses became the characteristic buildings of Otaru.

The iconic Otaru Canal was created between 1914 and 1923 to increase the efficiency of loading and unloading kitamae-bune, which increased in number every year. As the port was not equipped with a wharf, anchored ships were loaded and unloaded by barges going back and forth. When the wharf was completed in 1937, the canal lost its function. Then, with the establishment of the new port of Tomakomai, the number of ships calling at Otaru Port declined sharply and the area around the canal declined further, as did Otaru City, called “Declining Sun Town” during this period, with the canal being seen as a symbol of this decay. After 10 years of controversy over whether to keep or destroy the canal, it was finally decided to bury half of it for the road while the other half would become the promenade as we know it today, making Otaru a tourist destination.

A good way to immerse yourself in the history of Otaru is to visit the Otaru History and Nature Museum, housed in an old warehouse near the canal. The museum is divided into two main exhibits: one featuring historical artifacts, the other highlighting the surrounding nature. In the exhibition hall, you can see a reproduction of a kitamae-bune, the products they carried, maps, paintings and photos describing the history of these trading ships. There is also a corner dedicated to herring fishing and a replica of a street in Otaru at the beginning of the 20th century, when the city was most prosperous. All explanations are in Japanese only, but the museum provides explanatory notes in English that will help you understand the exhibits and thus enjoy the museum visit. The second exhibit focuses on presenting the nature of Otaru and Hokkaido and also features Jomon (Japanese prehistory, Jōmon meaning”cord-marked” and refers to pottery decorated by printing cords on the surface of wet clay) pottery with an interactive corner where you can try your hand at the fire making process or the rope patterns’ pressed into the clay of Jomon clay pottery. This museum (300 JPY) is really interesting with many models and exhibits that make this museum easily accessible.

Mochi is a rice cake made by pounding steamed glutinous rice into a paste. This method of making mochi originated from China and was introduced in prehistoric Japan soon after the cultivation of rice. During the 6th century, mochi making became popular with the development of the earthenware steamers. From the 8th century mochi began to be used in Shinto (a polytheistic belief centered on the kami, supernatural entities believed to inhabit all things. It is considered animistic because of the link between the kami and the natural world. The kami are worshiped in household shrines, kamidana, or public shrines, jinja) celebrations of births and weddings, as well as in New Year festivities. The nobles of the imperial court believed that freshly prepared mochi symbolized long life and well-being. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the custom of kagami mochi (mirror mochi) appeared among the samurai class. The kagami mochi (see picture below) consists of two spheres of mochi stacked on top of each other, topped with a bitter orange. The two mochi discs are supposed to symbolize the year that is ending and the year that is coming, the human heart, the “yin” and “yang”, or the moon and the sun. The orange, whose Japanese name daidai means generations, symbolizes the continuity of a family from generation to generation. To welcome the new year, samurai would place them in the tokonoma (an alcove in a traditional Japanese room where art or flowers are displayed) to pray for their family’s prosperity in the new year. Even today, mochi plays a particularly important role in New Year’s celebrations, and Japanese households traditionally display a kagami mochi ensuring happiness and prosperity for the coming seasons. This chewy food is also a regular ingredient in festive dishes like zōni, a hearty soup that Japanese eat on the morning of the first day of the year.

As I explained, Otaru developed as a distribution base connecting Hokkaido and Honshu, Japan’s main island, with the arrival of a large number of cargo ships, and many of its residents worked on the docks, loading and unloading goods, particularly physical labor. It is not surprising that the favorite food of the dock workers was mochi, which was cheap, easy to carry and filled the stomach quickly! In fact, the caloric content of a square-sized piece of mochi is comparable to that of a bowl of rice. Not only Otaru dock workers enjoyed mochi, but Japanese farmers were also known to eat it during winter to increase their stamina, while samurai carried mochi on their expeditions because it was easy to transport and prepare.

Otaru, as the main port of Hokkaido, was a distribution base for ingredients such as rice, red beans and sugar, which are the raw materials for making rice cakes. Since mochi is part of Shinto rituals in Japanese daily life, the demand for mochi also increased as the city developed and its local population grew. When the Otaru Canal was completed in 1923, the port became even more lively, and many workers gathered in Otaru for unloading and transportation. Mochi shops were established in every small community to meet the demand. Rice cake production in Otaru was also supported by peddlers who were active until about the 1960s. At that time, the peddlers were called “gangan troops” and traveled by train to coal-producing areas in various parts of Hokkaido. They would pack their goods (agricultural and seafood products) in cans and trade. Of course, before leaving the developed city of Otaru to travel to the inland areas of the island, they used to purchase the most difficult products to get outside the city, such as mochi, at the Otaru market.

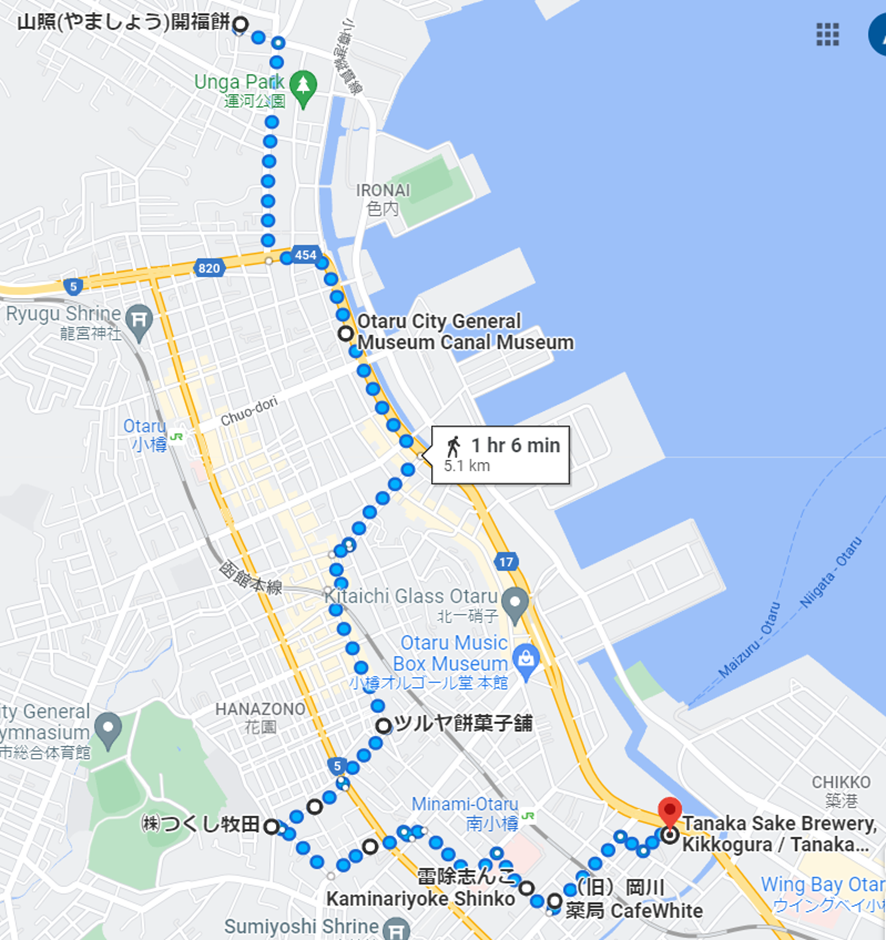

In order to get fresh mochi, we got up early and visited the 6 stores below by car, according to their opening time (between 5:30 and 9:00 am). But if you do this visit on foot, it is better to start it around 8:00 am which will allow you to avoid the round trips, by following the order of visit that I recommend on the map… But at the risk of seeing the stalls of the most popular stores empty.

You can do this gourmet tour by foot, it is a 5 kilometers stroll and will take you around 1.5 to 2.5 hours, the time to eat the mochi you purchase on the way.

①Kaminariyokeshinko (雷除志ん古)

②Minato Mochi store (みなともち本店)

③Keiseibeikashou (景星餅菓商)

④Tsukushi- Makita (つくし牧田)

⑤Tsuruya Mochigashiho (ツルヤ餅菓子舗)

⑥Kaifuku Mochi (開福餅)

Recommended order of visits:

①Kaifuku Mochi (開福餅)

● Otaru City General Museum Canal Museum

②Tsuruya Mochigashiho (ツルヤ餅菓子舗)

③Minato Mochi Honten (みなともち本店)

④Tsukushi-Makita (つくし牧田)

⑤Keiseibeikashou (景星餅菓商)

⑥Kaminariyokeshinko (雷除志ん古)

● CafeWhite(旧 岡川薬局 )

● Tanaka Sake Brewery, Kikkogura (田中酒造亀甲蔵)

①Kaminariyokeshinko (雷除志ん古)

Mochi making people usually wake up at 4:00 am in order to have mochi ready by 8:00 to 9:30 am. The stores close once all the mochi are sold. We started our tour of the mochi shops arriving at 7:30 am at the first shop, Kaminariyokeshinko, the oldest rice cake shop in Otaru, established in 1895. This store’s mochi are so famous that customers line up at 7:00 am and it’s not uncommon for just after 8:30 am all the mochi to be sold out! In this store, we bought three different daifuku, all made with koshi-an, a sweet and creamy red bean paste.

Like me, some of you may be a little confused about the difference between mochi and daifuku, also called daifuku mochi, as they are very similar. Mochi is very chewy and was originally made only of glutinous rice. Daifuku looks like mochi, but it is not (exactly) mochi! The thickness of the skin of daifuku is much thinner than that of mochi, and its texture is really thin, smooth and very soft. There are many varieties, the most common being white, pale green or pale pink daifuku mochi filled with anko, red bean paste, like the 3 below. The daifuku are about 4 cm in diameter and are covered with a thin layer of rice flour (or corn or potato starch) to prevent them from sticking to each other or to the fingers. The ideogram of –fuku in daifuku mochi , originally spelled 大腹餅 and meaning thick-bellied

The walnut daifuku was extremely tasty. The mochi was so soft that it melted in your mouth without having to chew it like other mochi. The sweet and salty taste of the dough was perfectly balanced and the walnuts added a bit of texture and a very subtle cookie taste. This mochi was so light and airy that I could have eaten two or three pieces easily. It’s really hard for me to describe the taste of the mochi as the Japanese have 445 words to define the textures and tastes of food, compared to 77 in English! Eriko Kakudate described the taste as amajyoppai,甘じょっぱい, sweet and sour, the texture as fuwafuwa,ふわふわ, light and fluffy, and as she has a better knowledge of Japanese sauces and ingredients, she wondered if there was shoyu in the design of this mochi. I guess it’s a trade secret and we’ll never know!

Kusa mochi, also known as kusamochi or yomogi mochi, is made from the leaves of the yomogi plant, also known as Japanese mugwort, which gives it its bright green color. This mochi was considered a medicinal food, as mugwort was thought to stimulate fertility. The Japanese ate this mochi to wish health and well-being to the mother and her children. The kusa mochi began to be used as an offering for Hinamatsuri (Girls’ Day, March 3) because of its beautiful bright green color, which symbolises fresh greenery, but also because it represents health and longevity. The kusa daifuku had a beautiful green color, a slightly harder texture and was harder to chew than the walnut daifuku. I found the bitter taste of the mugwort combined with the slightly salty paste to be an elegant and simple taste, very representative of traditional Japanese sweets.

As a French person, I usually have a sweet breakfast of bread with butter and jam, cereals or pastries on weekends and I thought that a mochi breakfast would be really nice! Each daifuku costs 150 JPY and you really get full with one or two pieces. I could really change my eating habits and incorporate more mochi into my daily life!

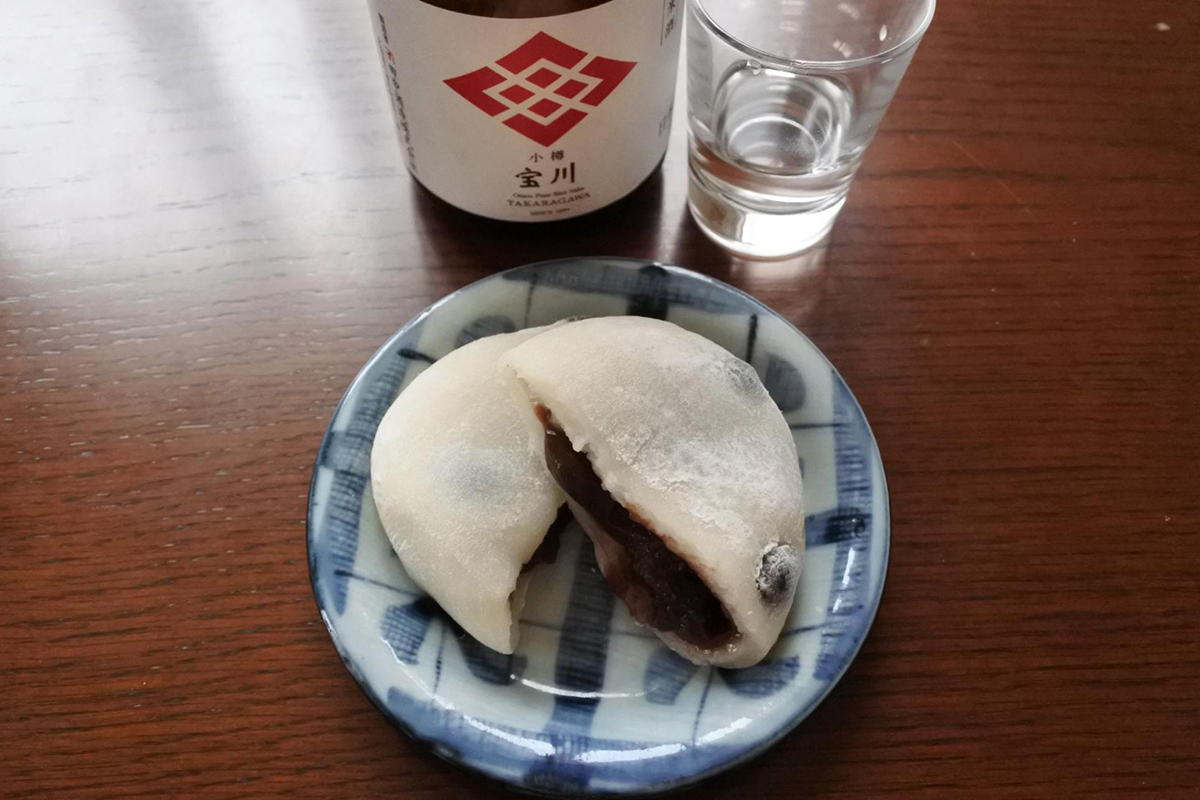

As mochi is a very consistent sweet, I ate the red bean daifuku later at home accompanied with some sake. It was really good with a perfect balance between sweetness and saltiness and the big black beans added even more consistency to this mochi.

②Minato Mochi store (みなと持ち本店)

This store, established in 1949, is a traditional wooden shop where you can feel the nostalgia of Otaru. We bought three mochi there: a pink daifuku, a kashiwa mochi and a kuro beko mochi.

I really liked the beautiful pastel color of the pink daifuku (160 JPY) which was a very soft mochi with a very elegant tasting core, perfectly balanced between sweet and salty.

The kashiwa mochi from this shop was a white mochi wagashi surrounding a sweet filling of white bean paste with miso (a traditional Japanese seasoning, produced by fermenting soybeans), wrapped in an oak leaf, kashiwa in Japanese, from which this mochi takes its name. Unlike the cherry blossom leaf used in sakura mochi, the oak leaf used in kashiwa mochi is not edible. However, its pleasant earthy aroma is transferred to the mochi and it is very pleasant. As oak trees do not shed their old leaves before new ones grow, the Japanese consider oak trees to be a symbol of the prosperity of their descendants and so this leaf is used to symbolize the prosperity of its descendants. On May 5, as part of Children’s Day in Japan, a holiday where children are celebrated and honored, kashiwa Mochi is eaten.

If you want to try a typical Hokkaido mochi, a Japanese confection that will take you back in time, I recommend you try beko mochi. There are many theories about the origin of the word beko. Some believe it refers to the black and white pattern of the Holstein, a breed of dairy cattle, known locally as beko, while others believe the name comes from the brown color, bekko, of caramelized sugar. The beko mochi has an elegant leaf shape and is made of a dough kneaded and steamed from two types of rice flours (glutinous and non-glutinous). The dough is sweetened (white sugar for the white dough; dark brown sugar for the brown dough). It is a simple delicacy that families used to prepare at home using small wooden molds that have been passed down from generation to generation. Beko mochi, a very hearty confection that is slowly digested despite its small size, has always been appreciated by the population as a source of energy.

③Keiseibeikashou (景星餅菓商) was established in 1913.

In this shop we bought a beko mochi and it is really difficult for me to describe its taste. I can only compare it to a candy I ate as a child: reglisse. Just like beko mochi, liquorice has a very consistent dough and a bitter and sweet taste at the same time. This candy is debated, either you like it or you don’t.

④Tsukushi- Makita (つくし牧田)

This shop sells, among other things, nerikiri wagashi and offers a wagashi making experience. These sweets made from rice flour, agar and anko (red bean paste) are handmade and are usually served at tea ceremonies. The roots of wagashi go back more than two thousand years, when mochi, considered Japan’s oldest processed food, was first made. Wagashi has evolved over time, shaped by interaction with China, the development of the Japanese tea ceremony and the arrival of Western confectionery. The Edo period (1603-1868), marked by a policy of national isolation, was a time when all aspects of Japan’s unique culture were enriched and wagashi developed and became popular during this period. Then when trade between Japan and the outside world intensified during the Meiji period, new wagashi were born with the invention of more and more types.

These elegant Japanese sweets have become a unique expression and celebration of Japanese culture! The term wagashi (Japanese sweets), coined during the Meiji period (1868-1912) to differentiate from European sweets after the end of Japan’s isolationist period, is used for all traditional Japanese desserts. From simple mochi daifuku to street foods like taiyaki (A Japanese cake shaped like a sea bream (the fish is called tai in Japanese) from which it takes its name. The most common filling is red bean paste made from sweet azuki beans), to the more classic nerikiri wagashi. Nerikiri, known for its beautiful appearance and delicate taste, is a type of Japanese wagashi made by kneading and mixing white bean jam, Chinese yam and glutinous rice flour. Nerikiri is an artistic Japanese confectionery, served at tea ceremonies, which is inspired by seasonal elements and can depict flowers, animals or traditional Japanese objects… Traditional wagashi uses only plant-based ingredients, and this is what makes these Japanese confections so different from Western desserts.

These desserts have a very sweet taste and go perfectly with bitter Japanese green tea or the earthy taste of matcha. These desserts are real little creations of art, with designs that change with the seasons! This culinary activity is an excellent introduction to Japanese culture, allowing you to learn more about the tea ceremony and the importance of the seasons in Japan. The Japanese take time to observe the changes in nature, especially during hanami, a period devoted to admiring the cherry blossoms, or in spring when the new green leaves appear, not forgetting autumn. In Hokkaido, people pay special attention to the color of the sky or the smells that differ according to the season. This attention is also reflected in the patterns of kimono belts, which change with the seasons. The Japanese calendar is organized around seasonal events that play an important role in the daily life of the Japanese. During this experience, you will also familiarise yourself with this world-famous Japanese delicacy. Let your creativity run wild as you create beautiful Japanese confections under the guidance of a professional. The wagashi shima enaga, the little bird that looks like cotton wool, is the island’s mascot and is very popular. They are so cute that you don’t want to eat them!

⑤Tsuruya Mochigashiho (ツルヤ餅菓子舗)

This rice cake shop has existed since the Taisho period (1912-1926). It is a large traditional wooden building and the front facing the street opens with sliding doors. We arrived a little before 9:00 am, the shop disappeared behind the drawn curtains and seemed closed. There were no signs indicating opening and closing times. I discovered that the sliding doors were not locked and I peeked inside discreetly. Two people were busy in the open kitchen behind the shop. A lovely lady greeted me and said that the shop would open in 15 minutes but that I could already order and buy. I told her I would come back.

When we came back 15 minutes later, the display cases were still empty, except for one that was filled with daifuku and kusa mochi. So we bought a piece of each (150 JPY per piece). There is also a huge mochi (1,430 JPY). Japanese people usually buy mochi of this size to share with their families during Shogatsu, the Japanese New Year. The color of the kusa mochi is particularly deep, and the slightly bitter taste of mugwort goes well with the sweet bean paste inside. The daifuku was tender and tasty, with a delicate balance. The lady gave us an extra daifuku. This shop is definitely worth a visit for the warmth of its owners.

⑥Kaifuku Mochi (開福餅)

Our last stop is a tiny shop, created in 1938, that opens directly onto the street with sliding doors. We ordered on the pavement, as we could not go any further into the shop, which contains only one display window. This showcase displayed all sorts of colorful sweets, including spring mochi. Eriko bought a sakura mochi and I bought an uguisu mochi (160 JPY) attracted by its pretty green color.

Uguisu is the Japanese name for the bush warbler, an Asian passerine bird more often heard than seen. The beauty of its song has earned it the English name Japanese Nightingale, although the Japanese warbler does not sing at night like the European nightingale. The call of the Uguisu male traditionally signals that spring has arrived in earnest. Uguisu mochi are made to admire the uguisu and to celebrate the arrival of spring; their shape represents the body of the uguisu, the color of the kinako, the green of its feathers. However, a real uguisu is not as light green as the green of the kinako.

They are made of gyuhi (rice flour kneaded for a long time with sugar or starch syrup which becomes a translucent paste) and an (sweet paste made of red azuki beans). The gyuhi covers the red bean paste and is shaped by hand into a slightly oval shape reminiscent of an uguisu. Its beautiful green color is obtained by mixing the gyuhi with mugwort (green) or sprinkling it with sweetened soy flour (yellow or yellow-green). The powder was very mushy and stuck to the palate but I enjoyed the taste of this mochi and the beautiful story around its making!

Sakura mochi is a Japanese confection consisting of pink-colored sweet rice cake with a red bean paste core and wrapped in a pickled cherry blossom leaf. Different regions of Japan have different styles of sakura mochi. This treat is traditionally eaten during the spring season, especially on Girls’ Day and during flower viewing festivals. The taste of this wagashi is slightly sweet and the salty taste of the sakura leaf gives it its unique taste.

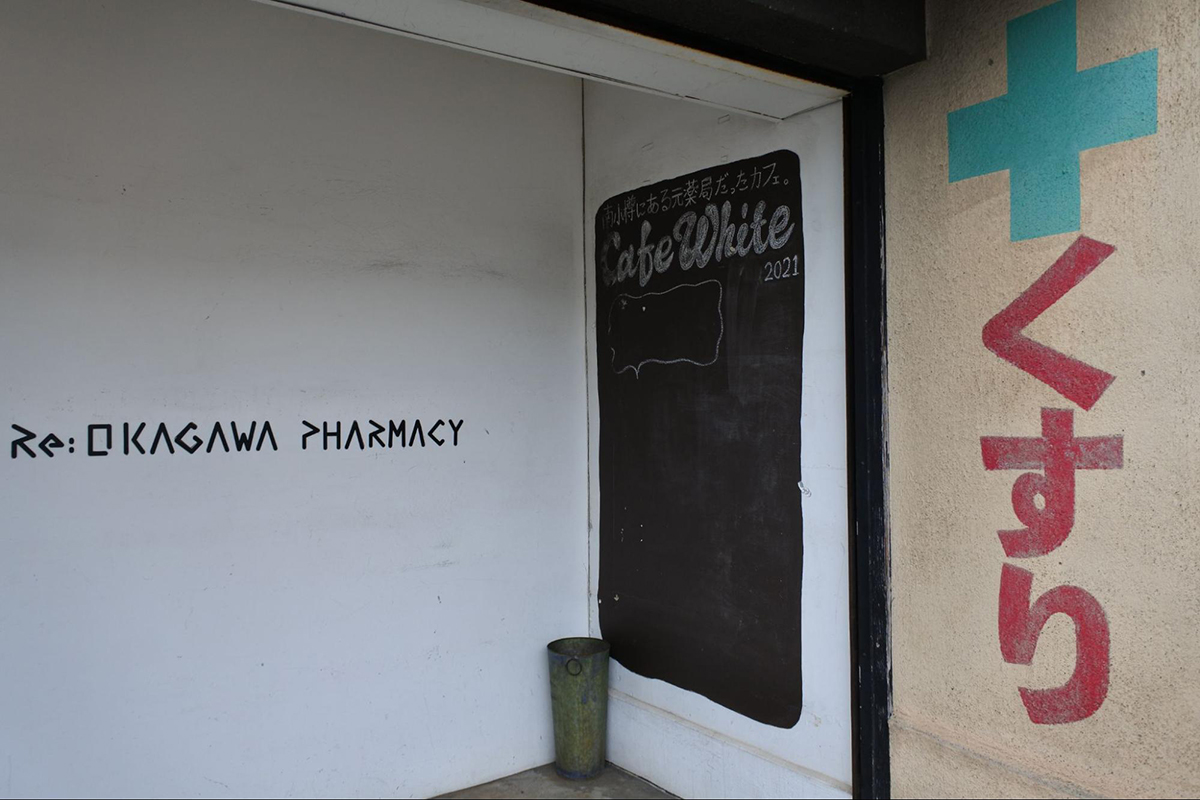

As surprising as it may seem, after this gourmet walk during which I ate 5 mochi (I ate the rest later at home), I still had room for lunch! Eriko had decided to try White Cafe (岡川薬局), a restaurant with an amazing concept! The Okagawa Pharmacy, built in 1930, was designated as the 32nd historic building in Otaru City as a Japanese-Western eclectic store building in 1993. This pharmacy was in operation for 4 generations before closing in 2005. A few years after its closure, it was planned to demolish the building, but thanks to the current owner, the old historical building was not dismantled but rehabilitated while preserving the urban landscape. This project participates in local economic development and “energizes the city” by continuing to mix various elements such as old and new, citizens and tourists. In 2017, the building received the Otaru City Streetscape Award.

Inside the building, which has a total area of about 300 square meters, there are many distinct spaces such as Café White, Gray Table which promotes coworking, and Apartment (Guest House). The building is divided into time and space, and each is operated differently around the three main services (Rent, Eat and Stay).

The café-restaurant, with white walls and tables, is nicely decorated with some remains of the old pharmacy and relaxing areas where you can play retro video games, listen to music or read the books provided.

We ended our gourmet stroll at Tanaka Sake Brewery, Kikkogura (田中酒造亀甲蔵). Kikkougura Sake Brewery takes advantage of Hokkaido’s cool climate and is one of the few sake breweries in Japan to produce a “four-season brew”, which is brewed all year round (usually brewing only takes place during the cold winter). The brewery takes advantage of the quality and abundance of Otaru’s water, which is a natural asset of the city due to its rich forests and surrounding mountainous nature. The groundwater comes from Mount Tengu. Outside the brewery, there is a well where you can taste the water which is known for its sweet and delicious taste. Rice is the main ingredient in making sake. The brewery has collaborated with local farmers to obtain high quality rice suitable for sake making, and uses only Hokkaido rice.

The main store, built in 1927, is a two-story wooden building that retains its ancient atmosphere. It is designated as a “historic building” in Otaru city. I learned about the various stages of sake making by visiting the brewery and tasted three kinds of sake at the store. I really enjoyed the light and refreshing aroma of Junmai Ginjo sake. I bought a small bottle of Junmai Takarakawa sake, “a pure and dry sake with a refreshing taste that spreads a light aroma and moderate umami,” to quote its label, to accompany the rest of the mochi !

I hope you enjoy reading this article. As Hokkaido experts, Eriko but also Kaori, Misa and I like to discover new places and together with the rest of our team at Hokkaido Treasure Island Travel create new authentic tours. Feel free to share your comments about this gourmet tour on our Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/hokkaidotreasure) and read our other article dedicated to Otaru (https://hokkaido-treasure.com/column/028/ ). We look forward to receiving your inquiry to help you plan a memorable trip to our beautiful Hokkaido!