Otaru is not a city that asks to be planned in advance. It does not require a fixed itinerary, a list of highlights, or a carefully allocated number of hours. Instead, it offers something quieter: a place that can be approached with minimal preparation and still make sense once you arrive.

For many travelers in Hokkaido, movement itself becomes part of the experience. Distances between cities are short enough to feel manageable, yet varied enough to require choices. Otaru sits comfortably within this rhythm. It does not interrupt a journey but rather settles into it, often as a natural extension of time already in motion.

Arriving in Otaru does not feel like crossing into a separate travel mode. The city does not demand attention all at once. Streets unfold gradually, and the scale remains human. There is no strong pressure to decide immediately where to go or what to see. Instead, the city allows visitors to orient themselves through movement—by walking, slowing down, and observing how spaces connect.

This ease of entry matters. In travel, especially when moving between multiple destinations, cognitive load accumulates quickly. Constant decisions—what to prioritize, how long to stay, what to skip—can turn even well-designed itineraries into sources of fatigue. Otaru reduces that burden. The city’s structure supports spontaneous decisions without penalizing them.

What makes Otaru particularly suitable as part of a broader journey is not a single attraction or historical narrative, but its adaptability. A short visit can still feel complete. A longer stay does not require additional planning layers. The city adjusts to the traveler’s pace rather than asking the traveler to adapt to it.

Otaru does not compete with other destinations in Hokkaido for attention. Instead, it complements them. It offers a different texture—one that is less about accumulation and more about continuity. This quality allows Otaru to function not as a destination that dominates an itinerary, but as one that quietly improves it.

Table of Contents:

1. Street Structure and the Experience of Walking

2. The Canal and the Role of Warehouses

3. The Port and Its Proximity to the City

4. Where Commerce and Daily Life Overlap

5. Craft and Its Distance from Everyday Life

6. How Otaru Fits Into a Broader Journey

1:Street Structure and the Experience of Walking

Otaru reveals itself most clearly at walking speed. The city’s structure does not reward rushing, nor does it require slow, deliberate sightseeing. Instead, it supports a steady pace that allows understanding to build naturally through movement. Streets connect without abrupt shifts in scale, and changes in atmosphere occur gradually rather than through dramatic transitions.

One of the first things visitors often notice is how little instruction is needed. There are signs, maps, and points of reference, but they rarely dictate behavior. Rather than telling visitors where to go next, the city suggests directions subtly through spatial cues—gentle slopes, the orientation of streets, and the way buildings open or narrow sightlines. Walking becomes a form of navigation that feels intuitive rather than analytical.

This structure reduces the need for constant decision-making. In many destinations, walking involves repeated micro-choices: whether to turn, whether to continue, whether something important is being missed. In Otaru, those concerns soften. Streets tend to loop back toward familiar areas, and dead ends are rare. Even when a route changes direction, it rarely feels like a mistake.

The physical scale of the city reinforces this comfort. Buildings are generally low to mid-rise, allowing the sky to remain visible and orientation to stay clear. Views are not blocked suddenly, and landmarks do not dominate the landscape. Instead, recognition comes from repetition—passing similar façades, noticing consistent materials, and becoming familiar with patterns rather than singular icons.

This environment encourages visitors to trust their movement. Walking without a clear goal does not feel inefficient, because the city is structured to return something in exchange for time spent moving. A short detour rarely feels wasted. Even when nothing “notable” appears, the act of moving through space contributes to understanding how the city works.

Importantly, Otaru does not penalize indecision. Stopping, turning back, or changing direction feels acceptable. The city does not create pressure to keep moving forward in a single line. This flexibility allows travelers to adapt their pace based on energy, weather, or time constraints without feeling that the experience has been compromised.

For travelers incorporating Otaru into a broader journey, this walking-based clarity is especially valuable. After navigating transportation schedules, accommodations, and transfers elsewhere, arriving in a place where understanding comes from simple movement can feel relieving. The city does not ask visitors to “learn” it before engaging with it. It allows learning to happen along the way.

In this sense, Otaru’s structure is less about efficiency and more about continuity. Walking becomes not just a means of getting from one point to another, but the primary way the city communicates itself. This communication is quiet, consistent, and forgiving—qualities that make the city particularly easy to enter, even with limited time or preparation.

2:The Canal and the Role of Warehouses

In Otaru, the canal does not announce itself as a destination that must be reached. It appears gradually, often after a period of walking during which the city’s rhythm has already settled. Rather than functioning as a climax, the canal operates as a pause—a space where movement slows not because it is required, but because the surroundings invite it.

What distinguishes the canal area is not spectacle but continuity. Warehouses line the water in a manner that suggests past function without demanding historical explanation. Their presence is readable even without context: solid structures built for storage and transport, positioned close to the water, aligned with the logic of movement rather than display. Visitors do not need to know dates or architectural terms to understand why these buildings exist where they do.

This restraint shapes how the canal is experienced. Instead of drawing visitors into a single viewpoint, the area allows for multiple ways of passing through. Some people slow down, others continue walking, and both responses feel equally valid. There is no implied “correct” way to engage. The canal does not insist on attention, and as a result, attention often arrives naturally.

Because the canal is integrated into the surrounding streets, it does not isolate itself from the rest of the city. Shops, small paths, and residential elements remain close by. This proximity prevents the area from becoming a separate zone that requires a mental shift. Visitors do not feel that they have entered a different category of space; they are still within the same urban flow, only slightly adjusted.

The warehouses themselves reinforce this sense of balance. Many have been adapted for contemporary use, but their scale and form remain legible. This allows visitors to understand adaptation as a process rather than a transformation. The buildings are neither frozen in time nor aggressively modernized. They occupy an in-between state that mirrors the city’s broader character.

Importantly, the canal area does not overload visitors with information. Explanations, when present, remain secondary to spatial experience. This choice reduces cognitive demand. Travelers who are already processing new environments, languages, and logistics are not asked to absorb additional layers unless they choose to. The canal can be appreciated through presence alone.

This design has practical implications for travel planning. Because the canal does not require a fixed amount of time, it fits easily into different schedules. A brief walk alongside the water can feel sufficient, while a longer pause does not require additional preparation. The experience scales naturally, adapting to the time available rather than defining it.

For travelers moving through Hokkaido with multiple stops, this flexibility matters. The canal does not compete with other highlights for attention. Instead, it provides a moment of alignment—a space where the journey can slow briefly without stalling. It becomes a connective element rather than a focal one.

In this way, the canal and its warehouses serve as an anchor without becoming an endpoint. They offer orientation rather than conclusion, allowing visitors to continue their movement through the city without feeling that something essential has been completed or missed. This open-endedness keeps the journey fluid, reinforcing Otaru’s role as a place that supports travel rather than dominating it.

3:The Port and Its Proximity to the City

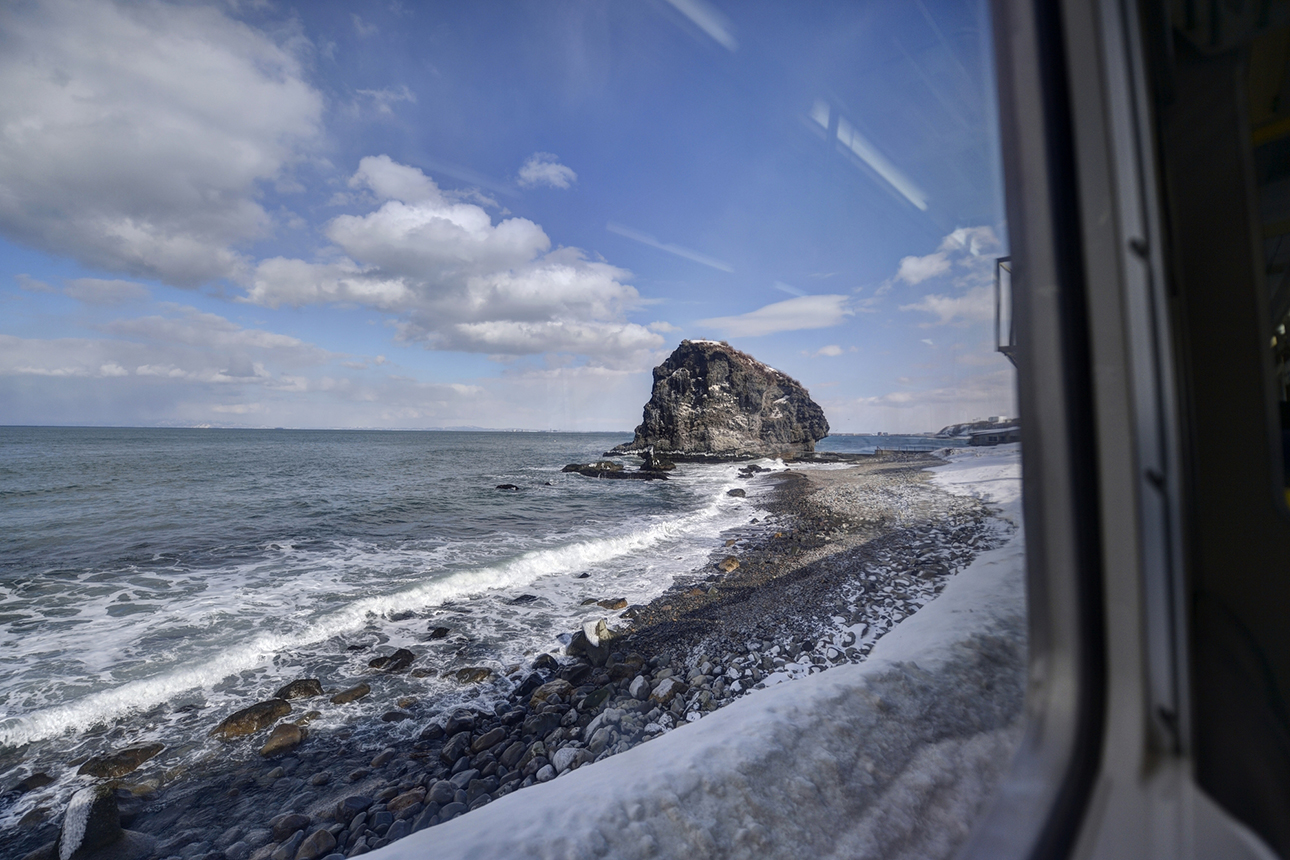

In Otaru, the port does not sit apart from the city as a separate destination. There is no clear moment of arrival that signals a transition from “city” to “harbor.” Instead, the port appears as part of everyday movement. Streets gradually open toward the water, and the presence of the sea becomes noticeable almost incidentally—through a shift in light, a change in air, or a widening of space.

This lack of separation shapes how visitors move. Rather than aiming for the port as a goal, many people encounter it while already in motion. The experience is less about reaching a point and more about realizing where one has arrived. This realization often happens without planning, which reduces the sense of effort usually associated with visiting waterfront areas.

The port’s infrastructure reinforces this relationship. Piers, working areas, and moored vessels remain visible, but they do not dominate the scene. These elements are readable without explanation. Even without understanding the specifics of maritime operations, visitors can intuitively grasp that the port is still functional, still connected to everyday activity, and not preserved solely for observation.

Because the port is not framed as a spectacle, attention shifts toward smaller details. Visitors may notice the texture of pavement near the water, the spacing between buildings, or the way streets align with the shoreline. These observations arise naturally when there is no single focal point demanding attention. The environment invites awareness rather than directing it.

Time plays an important role here. The port does not dramatically transform across the day, but subtle changes accumulate. In the morning, the area often feels open and quiet. By midday, movement increases slightly, blending local activity with visitors passing through. Toward evening, the pace softens again. None of these phases require scheduling. The port accommodates each without prioritizing one over the others.

This adaptability reduces pressure on travelers. There is no “best” time that must be targeted, no narrow window that defines the experience. As a result, visitors can arrive when it fits their broader itinerary rather than reorganizing plans around the port. This quality is especially valuable for those moving between destinations, where time is often fragmented.

The spatial relationship between port and city also affects orientation. Because the water remains close to the urban core, it functions as a reference point rather than a boundary. Visitors can use the shoreline to recalibrate their sense of direction, understanding where they are in relation to the rest of the city without consulting maps frequently.

Crucially, the port does not interrupt the city’s rhythm. It does not require a shift in behavior or mindset. Walking speed remains consistent, decisions remain minimal, and movement continues smoothly. The port becomes another layer within the city rather than an exception to it.

This integration explains why the port feels accessible even to those with limited time or energy. Visiting does not require commitment. One can pass through briefly, linger if desired, or simply acknowledge its presence before moving on. Each choice feels complete in its own way, without implying that something essential has been skipped.

In Otaru, the port’s value lies not in standing apart, but in staying close. Its proximity to daily life allows it to support the city’s overall ease of movement, reinforcing the sense that Otaru is a place where travel unfolds without friction.

4:Where Commerce and Daily Life Overlap

In Otaru, areas associated with commerce do not operate as clearly separated zones. Shops, small businesses, and everyday residences coexist along the same streets, often within the same buildings. This overlap changes how visitors perceive movement through the city. Rather than entering a district designed exclusively for consumption, travelers find themselves passing through spaces that continue to function for local life.

This structure reduces the sense of obligation that often accompanies shopping areas. In many destinations, commercial streets implicitly demand engagement—entering stores, making purchases, or following a prescribed route. In Otaru, those expectations are softened. Walking through these areas does not require participation. Observing, passing by, or simply continuing forward all feel equally appropriate.

Because daily life remains visible, the pace of movement stays moderate. Residents use the same streets for errands, commuting, or routine tasks, and this presence stabilizes the flow of people. Visitors tend to match this rhythm unconsciously. The environment discourages both rushing and lingering excessively, allowing movement to settle into a comfortable middle ground.

The physical design supports this balance. Shopfronts are generally modest in scale, and signage rarely dominates the streetscape. Buildings do not compete aggressively for attention. Instead of being pulled toward a single focal point, visitors distribute their attention across multiple small details—window displays, entrances, side streets, and the transitions between them.

This distributed attention has a practical effect. Travelers are less likely to feel that they must “cover” an area fully in order to understand it. Missing a store or skipping a block does not register as a loss. The experience remains coherent even when incomplete. This sense of sufficiency is important for those managing limited time or energy during a longer journey.

Another consequence of this overlap is flexibility in decision-making. Visitors can choose to enter a shop spontaneously, or decide not to, without disrupting their route. There is little need to backtrack or reorganize plans. Streets connect in ways that allow movement to continue smoothly regardless of small choices made along the way.

For travelers concerned about balance—between exploration and rest, between activity and pause—this environment is forgiving. One can stop briefly, move on, or change direction without feeling out of sync with the city. The absence of a dominant commercial agenda allows these adjustments to happen naturally.

Importantly, commerce in Otaru does not frame itself as the purpose of the visit. It exists as one layer among many, integrated into the broader urban structure. This integration prevents the city from becoming transactional in tone. Even when visitors do make purchases, those actions feel incidental rather than defining.

For those incorporating Otaru into a broader itinerary, this quality reduces fatigue. After destinations that demand attention or decision-making, moving through an area where engagement is optional can feel restorative. The city does not ask visitors to commit to consumption in order to justify their presence.

In this way, the overlap between commercial and residential life supports Otaru’s broader character. It reinforces the idea that the city can be experienced through movement alone, without obligations attached. This freedom allows visitors to remain present without pressure, keeping the journey fluid and sustainable.

5:Craft and Its Distance from Everyday Life

In Otaru, craft does not present itself as a subject that must be understood before it can be appreciated. It appears along everyday routes, often without announcement, integrated into spaces that remain open to ordinary movement. Workshops, small studios, and retail spaces coexist with streets used for routine passage, allowing craft to enter awareness gradually rather than through deliberate seeking.

This positioning changes the role craft plays in the travel experience. Instead of functioning as a highlight that requires time, explanation, or prior interest, it becomes part of the city’s background texture. Visitors may notice materials, tools, or finished objects without needing to pause. Recognition can happen in passing, and that recognition alone can feel sufficient.

The visibility of process is particularly important. In many cases, traces of making remain present—through partially finished items, tools arranged for use, or workspaces that feel active rather than staged. These cues offer context without instruction. Even without technical knowledge, visitors can intuit that making is ongoing, not preserved as a static display.

Because craft is not isolated in formal exhibition spaces, it avoids the pressure associated with evaluation. Visitors are not implicitly asked to judge quality, rarity, or authenticity. The absence of explanatory framing reduces the expectation that one must “learn” something in order to engage. Craft exists as an extension of daily life rather than a subject requiring interpretation.

This distance from obligation affects behavior. Visitors feel free to continue walking, glance briefly, or stop for longer, depending entirely on interest and energy. None of these choices carry consequence. There is no sense that skipping a workshop or not entering a shop results in a diminished understanding of the city.

The objects themselves often reinforce this relationship. Many are designed for use rather than display, even when their appearance is refined. This practicality makes it easier to imagine them as part of ordinary life, not just as souvenirs or symbolic items. Craft remains connected to function, which keeps it grounded in the present rather than anchored solely to tradition.

For travelers managing limited time, this integration matters. Engaging with craft does not require carving out a separate segment of the day. Encounters happen alongside other movement, allowing interest to emerge organically. If curiosity deepens, one can stop. If not, the journey continues uninterrupted.

This structure also prevents fatigue. In destinations where craft is framed as a core attraction, visitors may feel obligated to visit multiple sites or absorb detailed explanations. Otaru avoids this accumulation. Each encounter stands on its own, without implying the need for comparison or completion.

By keeping craft close to daily movement, the city allows it to function as a quiet indicator of local continuity. It suggests that making has not been separated from living, and that creative work remains embedded in ordinary routines. Visitors can sense this relationship without being asked to articulate it.

Ultimately, Otaru’s approach to craft aligns with its broader character. It offers presence without demand, information without insistence, and access without obligation. Craft becomes another way the city supports a low-pressure experience—one where understanding grows naturally, and engagement remains optional.

6:How Otaru Fits Into a Broader Journey

Otaru works best when it is allowed to remain flexible. The city does not require visitors to decide in advance how much time it deserves, and this openness is one of its most practical strengths. Whether approached as a short stop or a longer pause, Otaru adjusts without resistance. The experience scales naturally, expanding or contracting according to the time available.

This adaptability begins with access. Routes into the city are straightforward, and arrival rarely feels complicated. Once there, movement remains simple. Streets connect logically, and major areas sit close enough together that visitors do not need to segment their day rigidly. The absence of forced sequencing—no fixed order in which places must be seen—reduces planning pressure immediately.

Time management becomes intuitive rather than strategic. Visitors can gauge their stay based on energy, weather, or onward plans instead of obligations. If the day runs shorter than expected, the experience does not feel truncated. If extra time opens up, the city offers room to absorb it without requiring new decisions or adjustments.

This quality is particularly valuable within a broader Hokkaido itinerary. Travel across the region often involves multiple destinations, each with its own demands. In that context, Otaru acts as a stabilizing element. It does not add complexity to an already layered journey. Instead, it provides a moment where movement can slow slightly without stopping altogether.

Another factor contributing to this ease is the city’s consistency. Unlike destinations that peak sharply around a single attraction or time of day, Otaru maintains a relatively even rhythm. Visitors are not pressured to arrive at a specific hour or chase fleeting moments. This steadiness allows the city to fit into different travel styles, from loosely structured exploration to carefully paced schedules.

The city also accommodates changes in plan gracefully. Deciding to leave earlier, stay longer, or adjust direction rarely results in friction. There are few situations where a missed opportunity feels critical. This reduces the emotional cost of travel decisions, allowing visitors to remain present rather than focused on optimization.

For travelers who value balance, Otaru offers relief from accumulation. It does not demand that every hour be justified through activity. Resting, walking without purpose, or simply transitioning between places can all feel legitimate. This acceptance of low-intensity engagement helps preserve energy for the remainder of a journey.

Importantly, Otaru does not position itself as a destination that must define the trip. It complements rather than competes. By fitting easily into an existing route, it enhances continuity instead of breaking it. The city becomes part of the journey’s flow rather than a separate chapter that needs to be contained.

In the end, Otaru’s greatest strength may be its ability to remain supportive without asserting itself. It offers structure without rigidity and access without demand. For travelers navigating multiple stops and shifting priorities, this quality transforms Otaru from a place that must be planned into one that can simply be entered—and left—without strain.

This column is produced by Hokkaido Treasure Island Travel Inc., a Japan-based travel company.